Introduction

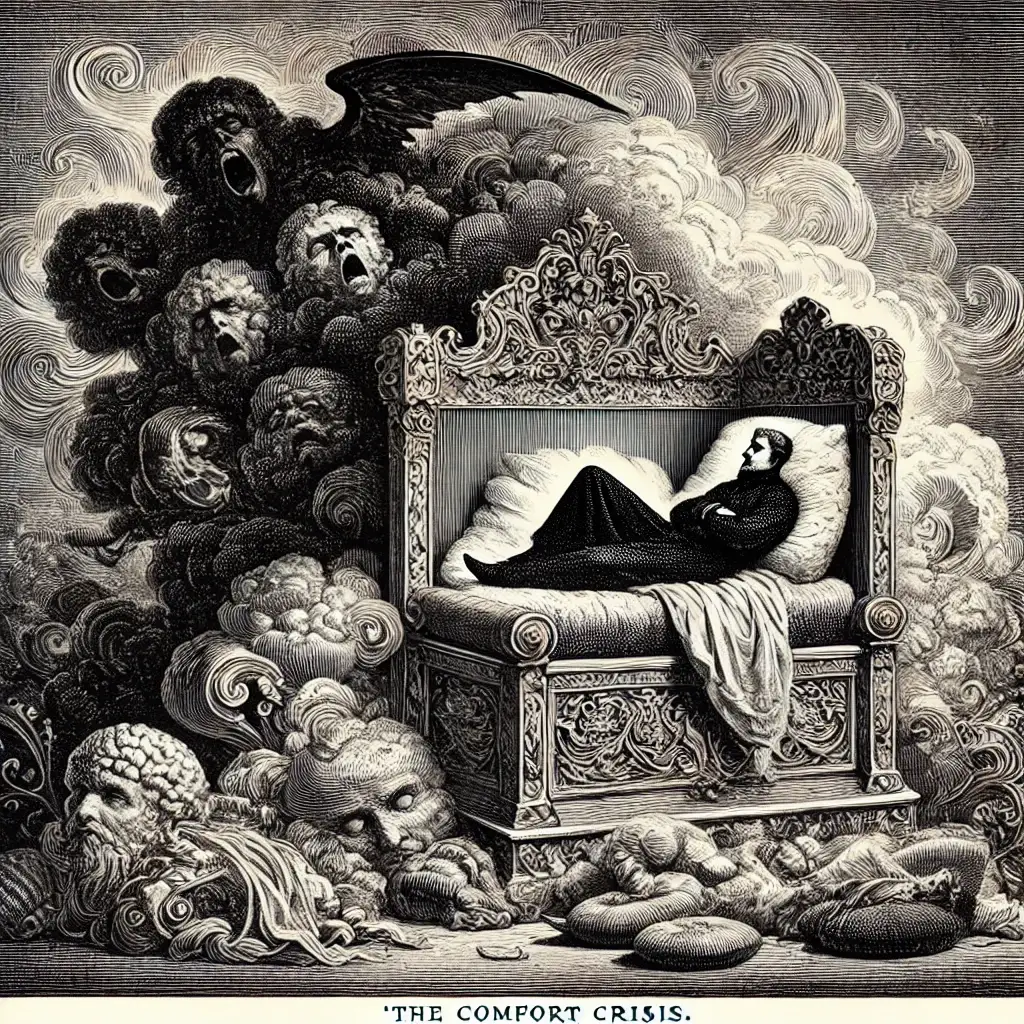

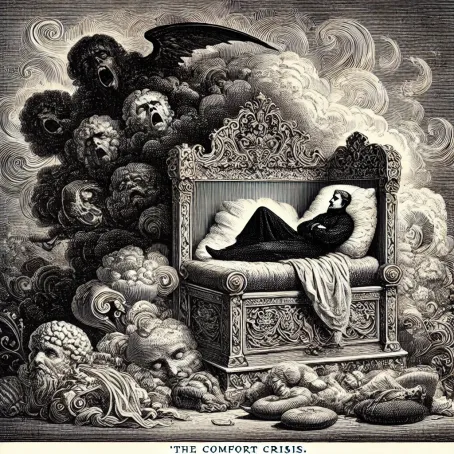

We are living in the most comfortable time in human history. And it’s killing us. Not quickly – there’s nothing dramatic about this slow death. It’s the quiet erosion of our physical capabilities, mental fortitude, and spiritual depth. The comfort crisis isn’t about luxury or indulgence; it’s about the systematic removal of beneficial stressors that humans evolved with for millennia.

Michael Easter’s excellent book “The Comfort Crisis” provides a comprehensive exploration of this topic and is highly recommended for anyone interested in understanding how modern comfort affects our wellbeing. While we’ll be expanding on some of these concepts, Easter’s work offers valuable insights and practical approaches to reintroducing beneficial stress into our lives.

The comfort crisis extends beyond physical challenges into our social connections, spiritual development, psychological resilience, and relationship with technology. By examining these additional dimensions, we can develop a more comprehensive understanding of how systematic comfort-seeking affects every aspect of human experience – and more importantly, how we can reclaim our inherent capacity for growth through strategic discomfort.

The Forgotten Language of Discomfort

For 99% of human existence, discomfort wasn’t optional – it was the baseline of daily life. Our ancestors walked miles daily, endured seasonal food scarcity, weathered temperature extremes without climate control, and faced genuine threats that demanded immediate action. These environmental pressures weren’t just challenging; they were the very forces that shaped our biology and psychology.

The human body and mind were forged through intermittent hardship. We evolved to thrive not despite stress but because of it – when that stress comes in appropriate doses followed by recovery. This biological principle, hormesis, is foundational to our development: small, manageable stressors make organisms stronger.

But what happens when those stressors disappear?

The Symptoms of Too Much Comfort

The evidence surrounds us:

- Physical degradation: Despite abundant food and medical advances, we face epidemic levels of obesity, metabolic disease, and reduced physical capability. The average American walks less than half the daily steps of our recent ancestors.

- Mental fragility: Anxiety and depression rates continue to climb despite unprecedented material comfort. Many struggle to handle even minor setbacks or inconveniences, their resilience muscle atrophied from lack of use.

- Spiritual emptiness: The existential void grows as we replace meaningful struggle with endless distraction and instant gratification. The deep satisfaction that comes from overcoming genuine challenge has become increasingly rare.

- Diminished community: When survival is no longer a collective enterprise requiring cooperation and shared hardship, our connections weaken. The bonds forged through mutual struggle are fundamentally different from those created through shared comfort.

Our environment now protects us from nearly all beneficial stressors: temperature-controlled buildings shielded us from heat and cold; on-demand food eliminated hunger; transportation removed physical exertion; smartphones eliminated boredom and the need to navigate uncertainty.

Each convenience, taken alone, seemed like a reasonable improvement. Together, they’ve created a catastrophic removal of the very forces that make us robust human beings.

The Paradox of Comfort

The ultimate irony of the comfort crisis is that our pursuit of ease doesn’t actually make us happier or more fulfilled. We’ve gained convenience but lost purpose. We’ve eliminated physical hardship but created psychological fragility. We seek comfort as an end in itself, not realizing that meaning rarely resides in comfort – it emerges from challenge overcome.

Consider the counterintuitive evidence:

- Lottery winners return to baseline happiness within months

- Depression rates are highest in the most developed, comfortable nations

- The most memorable and meaningful experiences in people’s lives often involve significant challenge or even suffering

We’re learning the hard way that humans don’t thrive when life is easy. We need resistance to grow against. We need obstacles to navigate around. We need the contrast of discomfort to truly appreciate comfort when it comes.

Voluntary Discomfort: The Ancient Solution

This isn’t a new revelation. Ancient wisdom traditions understood the comfort paradox millennia ago:

- Stoics practiced deliberate discomfort (cold exposure, fasting, hard bedding) to build resilience

- Buddhist monks embraced ascetic practices to transcend attachment to comfort

- Christian mystics used voluntary hardship to deepen spiritual awareness

- Indigenous cultures worldwide incorporated rites of passage centered on enduring challenge

These traditions recognized what we’ve forgotten: voluntary discomfort builds the capacity to handle involuntary discomfort. By intentionally exposing ourselves to manageable hardship, we develop the resilience to face life’s inevitable challenges with equanimity.

Reclaiming Our Birthright

The path forward isn’t rejecting all modern convenience or romanticizing primitive hardship. It’s the deliberate reintroduction of beneficial stressors into lives that have become too comfortable:

- Physical challenge: Regular exposure to physical exertion that pushes beyond comfortable limits – whether through exercise, rucking (walking with weight), cold exposure, or fasting.

- Mental challenge: Embracing difficulties that demand focus, problem-solving, and persistence rather than seeking the path of least resistance.

- Spiritual practice: Disciplines that develop presence and transcendence through voluntary restraint – meditation, contemplative prayer, silence, or solitude.

- Community challenge: Shared hardship experiences that forge deeper connections than comfortable socializing ever could.

The beauty of voluntary discomfort is that it provides the benefits of stress without the catastrophic downsides of truly threatening situations. It’s controlled exposure – hormetic stress – that builds rather than breaks.

Call to Action

The comfort crisis won’t be solved through accidental hardship. It requires intentional practice – a conscious decision to embrace difficulty when ease is available.

Our ancestors had no choice but to be hard. We do have a choice – and therein lies both our privilege and our responsibility. We can choose the harder path, not because we must, but because we understand that within that choice lies the key to becoming who we’re capable of being.

The comfort crisis has weakened us. But voluntary discomfort can restore what was lost.

The question isn’t whether you can be comfortable. The question is: Can you be hard when being soft is always an option?